Fieldwork Techniques: a virtual excavation

Visiting an archaeological site can be dangerous and confusing. Students are confronted with simple questions like: Where should I go? What am I looking at? The virtual reality (VR) application Fieldwork Techniques (built for Oculus Go) allows students to get familiar with an excavation site before visiting. In this way, we aim for students to become aware of relevant risks and possibilities that are present on site and recognise what is going on when they go to their first real excavation.

Together with Jasper de Bruin (Assistant Professor at Leiden University’s faculty of Archaeology) and Ivo van Wijk (Archaeologists at Archol) we captured a real time excavation using 360°. This forms the basis of the interactive application Fieldwork Techniques that prepares students for the real deal.

Fieldwork Techniques | Project Details

Partner: Faculty of Archaeology, Ivo van Wijk (Senior Archeologists Archol) and Jasper de Bruin (Assistant Professor).

Main target group:First-year students of the course Field Techniques in the BSc program Archaeology

This project is a result of the 360° VR Pilot Program that was initiated by the Centre for Innovation in 2017. Aim of the program is to explore the potential of 360° video based VR experiences for teaching and learning in academic education. After selection, six pioneering applicants from different faculties at Leiden University were invited to take part. In each project, the applying faculty members acted as partner and together with the Centre for Innovation created an innovative learning experience for their educational challenge. Read more about the 360 VR Pilot here.

Educational Challenge

It is very difficult for students to imagine what an excavation looks like and what kind of activities take place during one. Experiential learning in archaeology through visiting sites and participate in excavation is the best way to gain knowledge and skill. When students start their study program Archeology, they visit an excavation site, but every excavation has its own unique challenges and features. While on an excavation one cannot grasp all of these at once, especially because students must also be aware of safety measures. Preparing students for what they can expect beforehand enhances the level of understanding when they do visit an archeological site, and this increases the value of the visit.

Not only does a VR introduction to a site increase the educational experience for the student, visiting an excavation with a large group of students is costly and time-consuming. Not only that, excavating is hindered by weather and time of year. In the absence of an excavation that can be used for teaching all year round, our goal was to find a solution that could be used when organizational issues delay a visit. Going into the field it is a crucial learning moment for first-year archaeology students, and we wanted to increase the quality of the learning experience and support teaching techniques using our expertise. Overall, our main challenge for this project was to create a way for students to experience a real excavation in an accessible, free and safe way.

Fieldwork Techniques, a real excavation captured

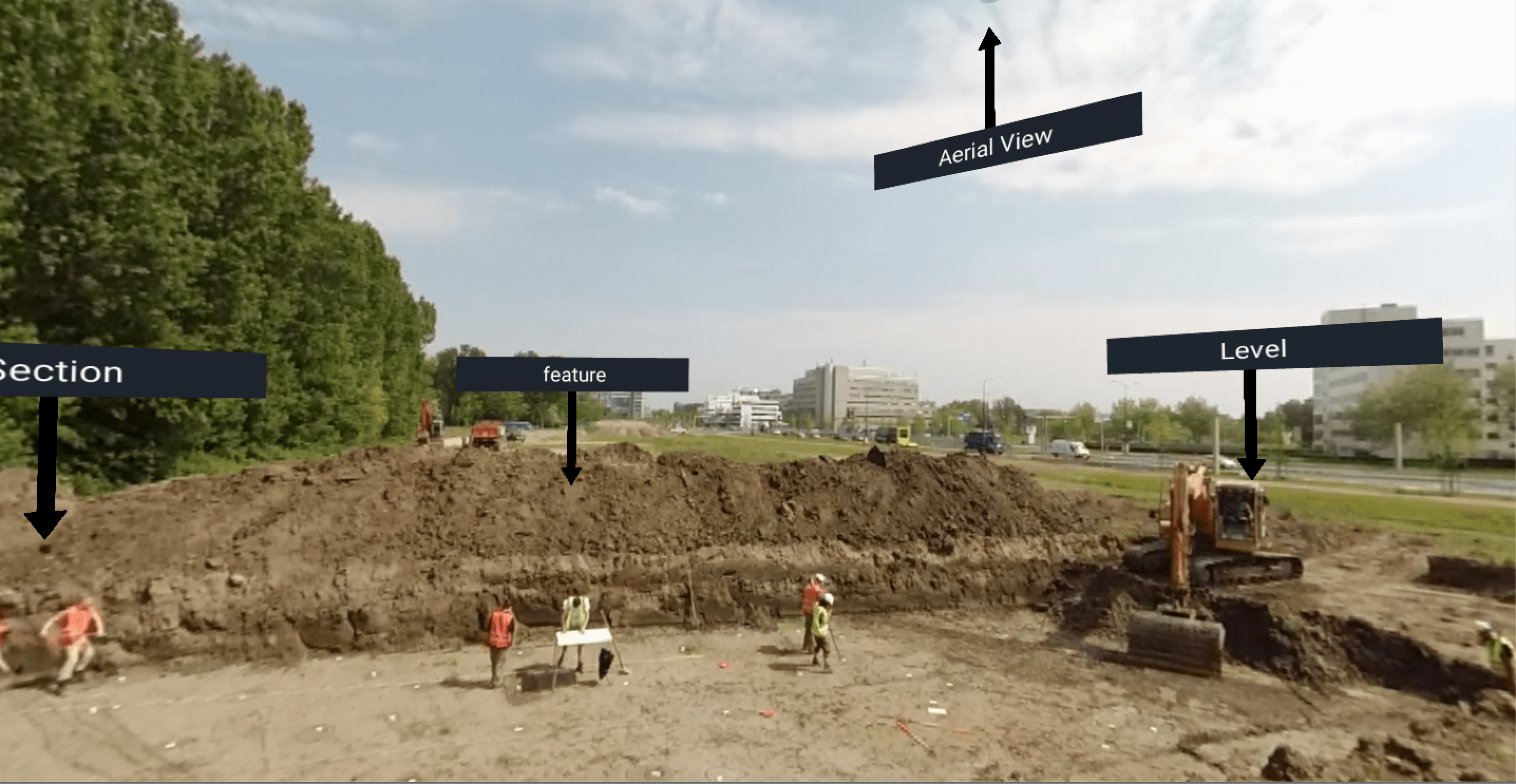

The solution we developed is a virtual tour around the terrain of an archaeological excavation. The recent excavation at the Plesmanlaan at the Leiden Bio Science Park was the setting for this experience and 360° video was used to capture every aspect of the excavation. The flow of the application is so that after getting an introduction by an expert archaeologist, users are invited to move outside towards the trench where they can select their position on the site and move from one hotspot to another.

Professional archaeologists working on site all have their own particular tasks. Each position (hotspot) in the virtual tour highlights different aspects of excavating (leveling the archaeological plane, documenting the features and making cross-sections over features are just a few examples). Users can freely decide the order in which they visit the highlighted locations and the amount of time they spent at each spot. This user control allows participants to zoom in on certain aspects to gain insight on how the methodologies they study in the classroom are applied in the field. Additionally, users get familiar with hazardous aspects of working on an archeological site.

Students view the entire experience in the classroom; a safe and controlled setting for students to experience a real life excavation without having to worry about getting in the way or destroying archaeological finds.

When starting the experience, students get an introduction to the excavation from inside the trailer.

When starting the experience, students get an introduction to the excavation from inside the trailer.  View from the edge of the trench. User can select positions to move to by clicking on the buttons.

View from the edge of the trench. User can select positions to move to by clicking on the buttons.Elimination in the design process

Based on input of Jasper de Bruin and Ivo van Wijk, we selected a set of the most important activities performed at an excavation. These activities formed the basis for the different highlighted locations available in the app. Not all of these were part of the working process on the day we visited the excavation to produce the videos, and the app experience reflects more possibilities than an experience on a real site. We decided to include additional locations so that the experience would be a ‘prototypical site’ and include as many aspects as possible. It was challenging to manage creating the desired scenes, and some archaeologists working on site who devoted their time to take part in the videos sometimes needed to act out activities.

Throughout the design process of this project, elimination was one of the main themes. At first, we designed the experience in such a way that each of the highlights was supported by an explaining voice over. However, when the first prototype was evaluated, we came to the conclusion that the experience without voice would fit the learning goal better. We found that adding a voice over hinders the feeling of being immersed in the situation and obstruct the movement of the user between scenes. We wanted to give students the opportunity to explore the site however they liked, and not feel prompted to actively observe. Because student users are already familiar with the methodologies they observe in the app, we decided it would be more valuable for them to interact with the VR experience in a way that allowed them to independently relate to the knowledge. Outside of the use of the app, teachers organise a discussion activity to review observations made and supplement the individual experience in the app. Based on these overall learning needs, we decided to also provide the 360° videos to the lecturer to use as a tool during the discussion and reference specific parts of the video. Our solution here was context specific, and depending on the type of user, testing a version of the experience with a guiding voice over would be interesting in the future or for contexts where the user needs more in-app information.

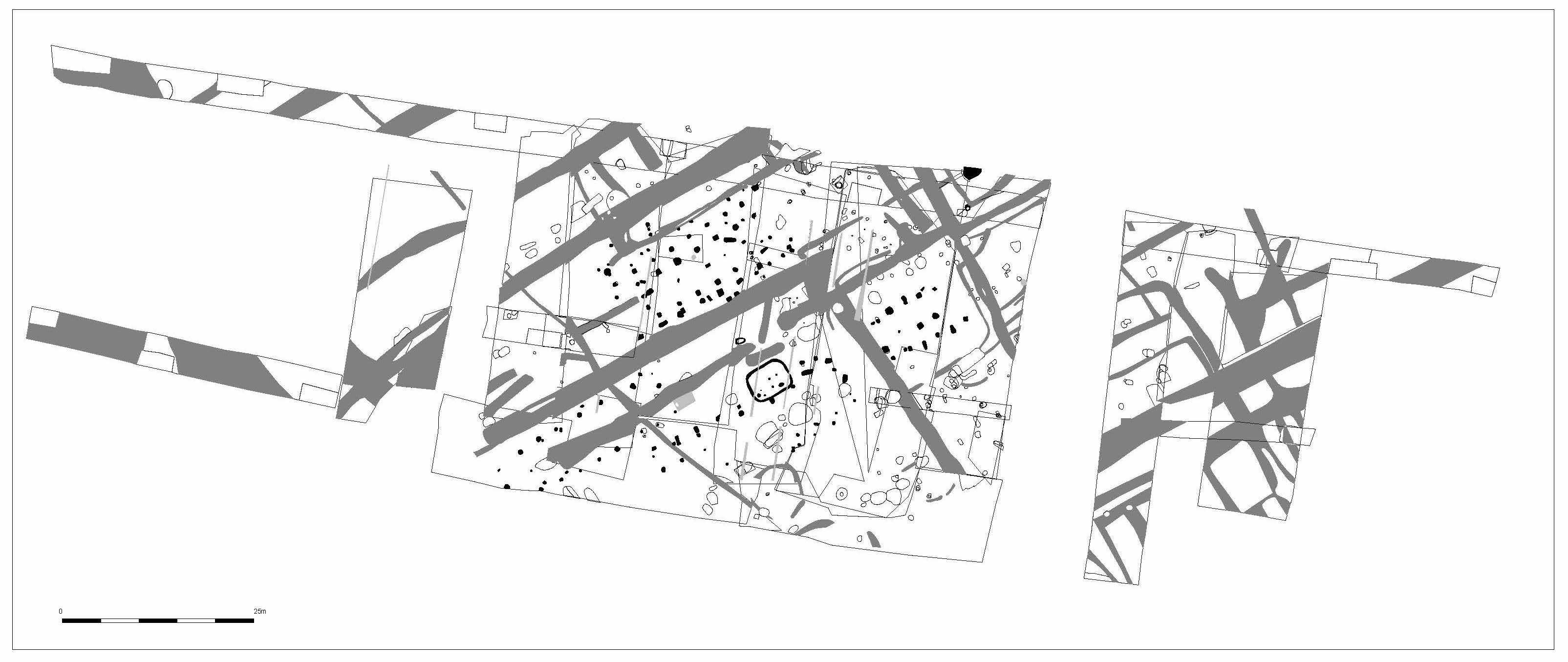

Another aspect that was excluded from the final result was the possibility of adding more interactive elements, like quiz questions and informational assets (e.g. example maps) into the vr experience. It turned out the initial design of a map implementation did not successfully instruct users on how to use the map, which meant they forgot the actual existence of the functionality, and readability of the map was low. Including a larger map at better resolution resulted in blocking a large part of the field of view on the 360° video, which in turn decreased the feeling of immersion. Therefore, we chose to give the teacher the option to provide maps of the excavation to students outside the vr experience.

Map of the area created during the excavation process. Students get access to the file so they can inspect the structure of the area in more detail after the experience.

Map of the area created during the excavation process. Students get access to the file so they can inspect the structure of the area in more detail after the experience. Hazardous factors are shown in the application as well such as this excavator taking care of taking of another layer of soil from the trench.

Hazardous factors are shown in the application as well such as this excavator taking care of taking of another layer of soil from the trench.Reactions and Implementation

The application has been received very positively by Ivo van Wijk and Jasper de Bruin, our partners and their students. It has been tested informally during the course Computational Methods as part of the Master of Science program Digital Archaeology. By doing this informal test, we were able to get feedback and practise implementing the experience so that it would be ready for use in the first-year’s bachelor target course: Field Techniques. We hope this project contributes to building a bridge between theory and practise for current and future archaeology students.

An interesting alternative use of the application is to use it as a tool to communicate information about excavations to stakeholders outside of the academic environment. For example, when a local municipality needs to give permission to start an excavation, the exporting or interested parties can use the tour to share knowledge on how an excavation functions in practise. Interested parties can then understand the methods used and discuss how excavation or construction plans may impact the environment. Lastly, we believe that the Field Techniques app has the potential to educate the general public about what is actually going on at an excavation, and allow those interested in archaeology to have a meaningful and educational experience.