Insights

Virtual Exchange, Genetic Privacy and the Evolving Role of the Humanities

Robert Zwijnenberg can offer his course in three different ways: not only as a MOOC and as a blended on-campus course, but also as an online course for credit that can be followed remotely by students from partner universities. The Centre for Innovation sat down with Zwijnenberg to discuss his motivation for participating in Virtual Exchange and for developing his innovative course, and his experiences until now.

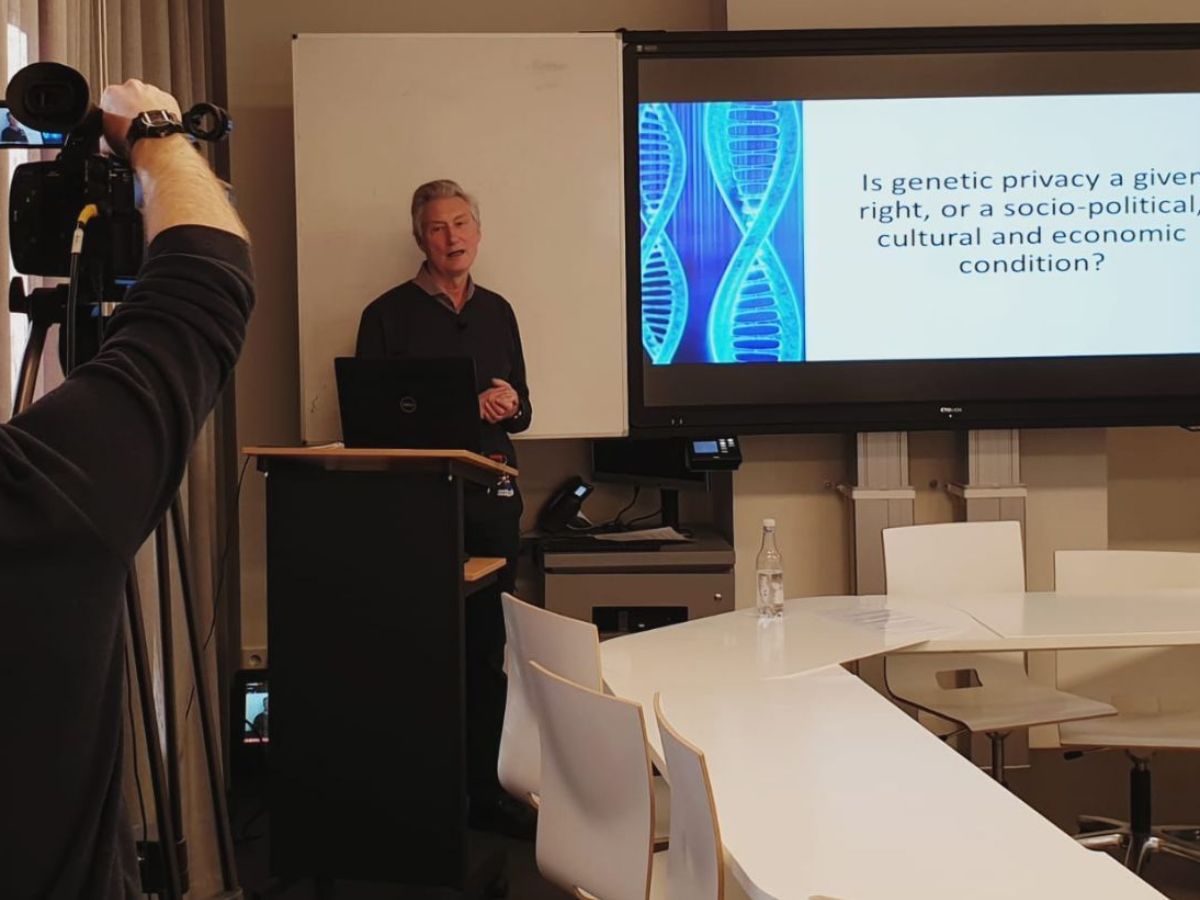

Last year Robert Zwijnenberg (professor in art and science interactions at Leiden University) has developed a MOOC about Genetic Privacy for a worldwide audience. Now, he re-uses parts of the MOOC as study material for his on-campus students in a blended course about the same subject. Also, he opens up this course for an international group of virtual students, who participate in the course through Leiden University’s Virtual Exchange programme. Now, Zwijnenberg can offer his course in three different ways: not only as a MOOC and as a blended on-campus course, but also as an online course for credit that can be followed remotely by students from partner universities. The Centre for Innovation sat down with Zwijnenberg to discuss his motivation for participating in Virtual Exchange and for developing this course, and his experiences until now.

What were your main reasons for wanting to be involved in the Virtual Exchange project?

Genetic Privacy is a complicated concept, and your stance towards it is very much informed by your personal understanding of the term, your cultural background and your geographical and socio-economic position. Through Virtual Exchange I can invite students from all over the world, with diverse backgrounds and attitudes towards the subject, to virtually participate in the course, and to share their opinions with my on-campus students. This multiplicity of perspectives in my classroom enriches the debate around genetic privacy, and allows for a more in-depth discussion on the subject to take place. It also allows students from Leiden University, who are often used to think along the lines of a liberal Western point of view, to reflect on their own position, and to get out of their own bubble. This helps us foreground the complexity of the debate around genetic privacy.

Your course Genetic Privacy: Should we be concerned? started off as a MOOC (Massive Open Online Course), that has been published on the online education platform Coursera. What made you decide to take your MOOC back to the campus?

It was a great experience to create the MOOC! But, there’s much more to say about the subject as genetic privacy is quite an ambiguous concept, and the ethical debate around it is highly complex. When you publish a MOOC on Coursera you are in a way, of course, restricted to the platform they offer, which limits the possibilities for assignments and discussions. So I wanted to see how I could facilitate a more elaborate discussion on the topic than we did in the MOOC.

I also wanted to further innovate on-campus teaching methods. And I think that integrating online elements in campus education is one way of doing that. This, for example, allows you to discover and develop a new role for yourself as a teacher. I notice that many students, when I ask them a question, expect that I will give them the ‘right’ answer. With the subject of genetic privacy, however, there is no single correct answer but there are many. With newer course designs I hope to find new ways to stir discussion, and to change my role as a teacher from an allegedly authoritarian figure to someone who facilitates discussion and critically thinks along with the different views that students share in class.

Your Virtual Exchange course is created to facilitate discussion and collaboration between on-campus and online students. How did you incorporate this in the course design?

The course design was focused on offering both virtual and on-campus students an equal sense of involvement in the course. Therefore, we created discussion forums on Coursera and Blackboard on which all students could share their views and ideas prior to, and following each class. The idea was that students had to prepare each class by going through material in the MOOC – videos, podcasts or assignments – and that they would then immediately share a first reflection on the discussion board in Coursera. After class they were asked to post something on another discussion forum on Blackboard to dive deeper into the topic. These online discussions gave all students the feeling that they were necessary, it gave them a sense of responsibility which kept them involved.

We tried to increase this level of engagement by assigning on-campus students the role of moderators in class; they had to communicate the key points that were discussed during the lecture to their fellow virtual students. In turn, virtual students received additional reading material that enabled them to contribute more elaborate insights, to further substantiate the online discussion.

To enhance the interaction between on-campus and virtual students we created groups in which both types of students were asked to work together on one assignment. Some groups communicated about their assignment via the discussion forums, others also used WhatsApp. Together they had to work on creative blog-posts and video assignments which stimulated the groups to work together towards one collaborative result.

All lectures in the course were live streamed and recorded via Mediasite and published on Blackboard, so students who were unable to attend could watch them later on. And to make sure that virtual students would feel just as included and involved as on-campus students, all interaction during class was mediated by the tool PresentersWall, which allows students to post questions or comments on a live discussion feed. However, this meant that students who were physically in class couldn’t speak up, but had to ask their question via an external tool. This felt a bit awkward and unnatural for both the students and myself, so this is still something we have to improve and develop further. Perhaps in the future a wall full of screens, showing the virtual students’ faces might help alleviate these challenges.

We also clearly communicated the whole set-up of the course to all our students, so they knew what to expect. The course obviously has a different kind of set-up than students are used to, but by constantly repeating all the different steps in this course, and by giving students the space to provide their own feedback, we tried to keep in touch with them, so they would feel included in the course.

How would you describe, to someone without your kind of background, what genetic privacy is and why it is important to learn more about this topic and to have a debate on it? How do you address this in your Virtual Exchange course?

Genetic privacy is an issue that does not only affect an individual’s right to privacy, but has also to do with the choices that a society takes as a whole to run its affairs. In democratic societies, many dilemmas arise in terms of the circulation and collection of large amounts of personal (digital) data. What makes the discussion about genetic data so important and urgent, is that they also reveal information about family members – as they usually have similar genetic codes. This means that when your genetic material is filed in an (open access) database your family members can be linked to it, and it reveals information about their genetic makeup too.

The discussion gets even more complicated when there are public interests at stake. An example is the collection of DNA material to solve a crime. This was the case with the Golden State Killer, who was caught by comparing DNA found at the crime scene to data in a commercial genealogy databank. Critics point out that this causes innocent family members to get involved in the investigation without them knowing it. On the other hand, it is thanks to the availability of this material in a databank that a killer has been caught – which is in the interest of public safety.

Ultimately the question in this debate is: where do we place the border between individual autonomy and public interest? We also address this question in the course, as we ask students to formulate their own stance towards it and to think about how we as a society could regulate this issue with their personal stance towards genetic privacy in mind.

What opportunities do you see for the humanities in developments with regard to online learning?

The humanities bear the responsibility for educating and bringing together a diverse group of students and scholars who can reflect critically on developments in, for example, the field of biotechnology – on what it actually means that these developments take place, and what ethical questions they raise. Online learning can provide ways to bring together such a diverse group of people, including those that wouldn’t usually have easy access to university-level education – because of their geographical location and/ or socio-economic situation. It is important for everyone to have a voice in this kind of debates.